The Great ‘Expat vs. Immigrant’ Dust-Up: It’s Time to Face the Music (and the Dictionary)

Right then. Put down your lukewarm cup of imported PG Tips and pull up a chair. We need to have a chat.

If you’ve spent more than five minutes on any “Brits in Spain” Facebook group, between the desperate pleas for a plumber who works on dozens and someone trying to sell a 1998 Vauxhall Corsa with the steering wheel on the wrong side, you will have seen The Argument.

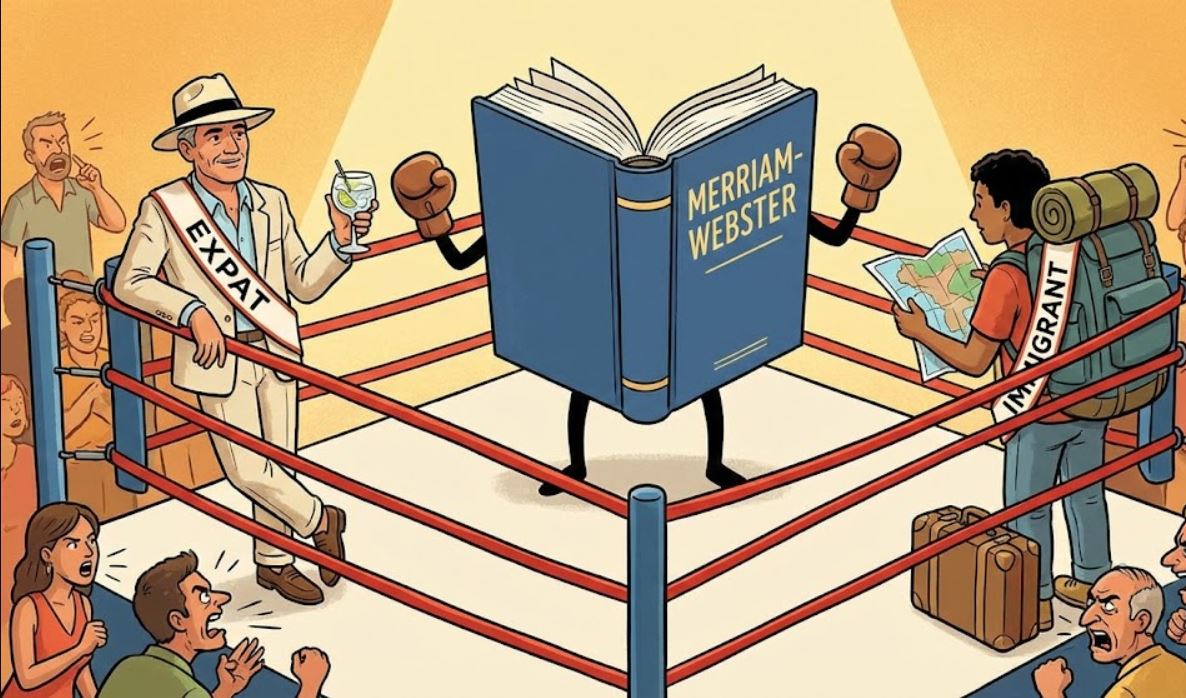

It’s the semantic fistfight that never ends. It’s the rumble in the jungle of the Costa del Sol comment sections. It is, of course, the great debate over labels: Are we “Expatriates” or are we “Immigrants”?

I’ve watched these online battles unfold with a sort of horrified fascination. It usually starts innocently enough. Someone posts a news article about post-Brexit residency rules, and uses the word “migrant” to describe the British community.

Suddenly, Gladys from Fuengirola (who hasn’t been back to the UK since the London Olympics) enters the chat in ALL CAPS. She is absolutely furious. She is not, she declares, an immigrant. Immigrants are people in dinghies, or those people Nigel Farage complains about. She owns a villa and contributes to the local economy by buying six bottles of gin a week at Mercadona. She is an Expat.

It seems to be a uniquely British affliction, this desperate need to distance ourselves from the I-word. We cling to the title of “Expat” like a life raft in a sea of Spanish bureaucracy. It sounds posher, doesn’t it? “Expat” conjures images of colonial administrators in linen suits sipping G&Ts on a veranda while ordering the locals about. It implies a temporary, slightly superior status.

“Immigrant,” on the other hand, sounds a bit… well, like hard work. It involves TIE cards, learning the difference between ser and estar, and actually integrating.

But look, I’m tired of the arguing. It’s ruining my morning tostada. So, I decided to do something radical. I decided to ignore Barry down the pub, ignore Gladys on Facebook, and go straight to an actual authority.

I consulted the dictionary.

I know, wild, isn’t it? Using facts to settle an emotional argument. But bear with me. To ensure total neutrality, I’ve gone with Merriam-Webster.

Let’s rip the plaster off quickly. Here is what Merriam-Webster has to say about the word Immigrant:

“A person who comes to a country to take up permanent residence.”

Read that again. Let it sink in.

Notice what it doesn’t say. There is no small print. There is no clause that says “unless you are British and enjoy a full English breakfast.” There is no exemption for people who own property in Torrevieja rather than renting a flat in Lavapiés. It doesn’t mention skin colour, bank balance, or whether you refuse to watch Spanish TV.

If you moved your life from drizzly Stoke-on-Trent to sunny Spain with the intention of staying here—if you went through the rigmarole of getting your green residency certificate or your shiny new TIE card—congratulations. You moved to a country to take up permanent residence. You are an immigrant.

I can hear the collective clutching of pearls from here to Alicante.

But wait, before you choke on your digestive biscuit, let’s look at the other definition. The one we prefer. What does the dictionary say about being an Expatriate?

“A person who lives outside their native country.”

Well, would you look at that.

Technically, yes—Brits living in Spain are expatriates. We are living outside our native country. Gladys was right! Huzzah!

But here’s the kicker, the massive elephant in the room that we’re all trying to ignore while sipping our cheap wine:

You can be both.

In fact, if you live here permanently, you are both. The Venn diagram of “British Residents in Spain” is just one big circle containing both definitions.

The difference isn’t legal; it’s purely psychological and, let’s be brutally honest, a bit egotistical. We use “expat” for us (wealthy Westerners moving to warmer climates for a nice lifestyle) and “immigrant” for them (people moving to our home countries out of economic necessity or safety).

It’s a double standard that smells worse than the drains in August. We happily complain about immigrants back in the UK “not learning the language” while living in urbanisations in Spain where English is the primary tongue and the only Spanish words known are “una cerveza, por favor” and “la cuenta.”

We need to get over ourselves.

When I go to the extranjería (the clue is in the name—the foreigners’ office) to renew paperwork, I am standing in the same queue as the Moroccan guy, the Colombian family, and the Ukrainian refugee. The Spanish government doesn’t have a special VIP “Expat” lane where they serve you tea and salute the Union Jack. To them, we are all the same: inmigrantes. Foreign residents.

So, let’s settle this once and for all.

Are you an expat? Yes, by definition. Are you an immigrant? Yes, also by definition.

Embrace it. Being an immigrant isn’t a dirty word. It takes guts to uproot your life and move to a new culture. It’s an adventure.

Let’s stop getting hung up on the labels and focus on the important stuff. Like why the Spanish insist on having dinner at 10 pm, or why nobody knows how a roundabout actually works.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, this immigrant is off for a siesta. It’s hard work being a foreigner.